GIRLS’ TOMATO CLUBS IN THE SOUTH: CULTIVATING MORE THAN TOMATOES

An interpretive overview for Cucina di Madre Terra, honoring our mission to preserve food and farming heritage.

WHAT THEY WERE

In the early 1900s, girls’ tomato clubs spread across the rural South as a practical, hands-on way to teach gardening, canning, record-keeping, and household enterprise. While boys often joined corn clubs, girls cultivated tomatoes on small plots—then preserved and sold the harvest. The result was a quietly transformative blend of education, nutrition, and community uplift that helped seed the broader youth extension movement later known as 4-H.

WHY TOMATOES, WHY GIRLS

Tomatoes fit the homestead. They thrive in small spaces, bear heavily, and lend themselves to safe home preservation. Teaching girls to grow and can tomatoes addressed seasonal hunger, added vitamins to household diets, and reduced waste through shelf-stable jars.

Girls shaped the home economy. Club work recognized girls as vital decision-makers in kitchens and gardens—domains that influenced family health, budgeting, and food security. By engaging girls, reformers aimed to modernize household practices and elevate domestic work as skilled, scientific, and respectable.

HOW THE CLUBS WORKED

THE ONE-TENTH-ACRE MODEL

Most members tended a one-tenth-acre plot. They selected varieties, prepared soil, managed pests, hoed, staked, and harvested—then measured yields, tracked costs, and calculated profit. This simple scale made experimentation and success achievable.

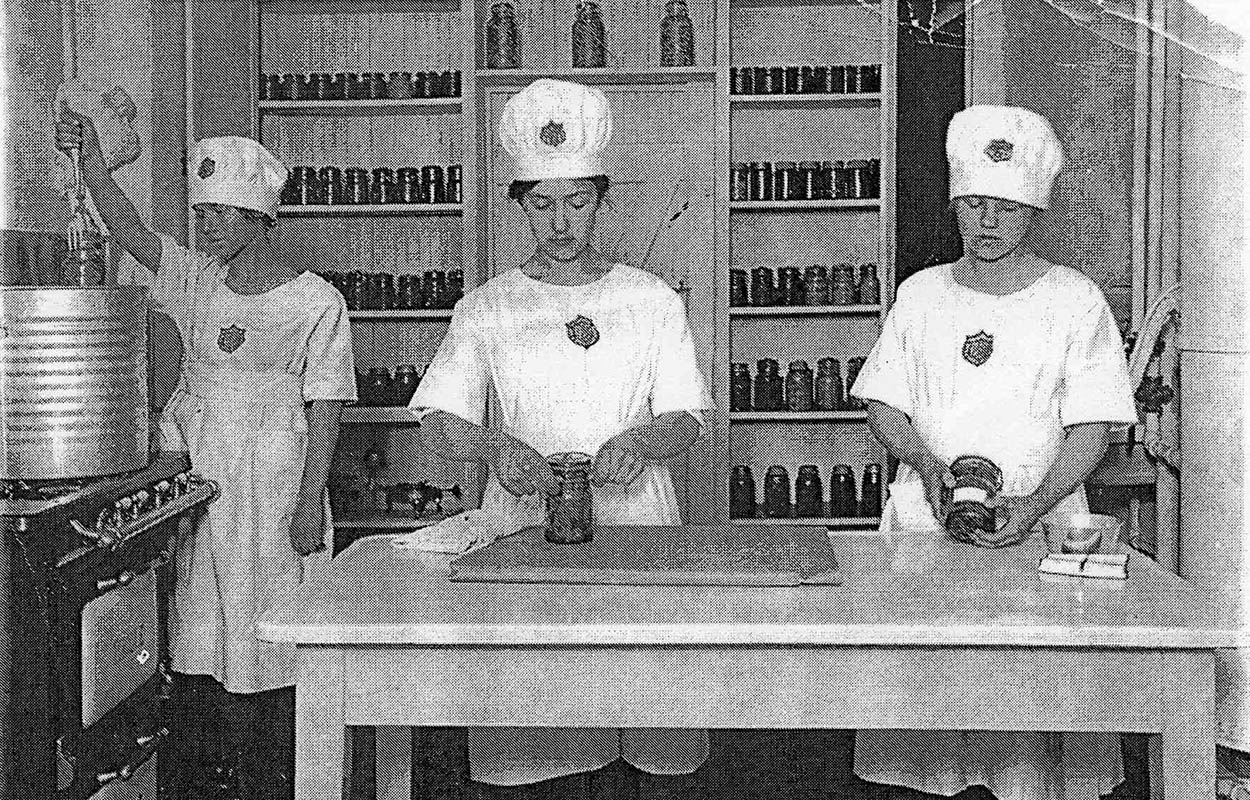

CANNING, SAFETY, AND SKILL-BUILDING

Instruction emphasized clean kitchens, proper equipment, and proven sterilization methods. Girls learned to schedule work around ripening fruit, batch tasks efficiently, and maintain strict records—habits that translated to reliable food stores and modest income.

COMMUNITY DEMONSTRATION AND PRIDE

Clubs met for field days, canning demonstrations, and exhibits. Ribbons and ledgers celebrated both quality and accuracy. Sharing techniques created peer networks that spread good practices household by household.

BENEFITS TO GIRLS

Confidence and competence. Members practiced scientific gardening, time management, and careful record-keeping. Success in the garden and pantry built a durable sense of agency.

Earnings and independence. Selling fresh tomatoes and canned goods offered spending money, savings, or help with school costs—an early taste of entrepreneurship.

Pathways forward. The discipline of planning, measuring, and presenting results prepared many for leadership in homes, classrooms, and community organizations.

BENEFITS TO HOME LIFE

Healthier, steadier food. Pantries filled with jars of tomatoes, juice, and relishes extended the growing season and diversified family diets with vitamins and minerals.

Stronger household economics. Home-preserved food reduced purchases, stabilized meals during lean months, and turned surplus into cash or barter.

Respect for domestic expertise. Treating kitchen work as skilled practice—worthy of instruction, measurement, and recognition—raised the status of everyday labor that sustains families.

BENEFITS TO THE COMMUNITY

Local know-how spreads. Demonstrations and fairs multiplied impact beyond individual plots. Neighbors saw safe canning practices and productive gardens in action.

Seeds of youth leadership. Clubs trained young organizers, record-keepers, and presenters—the kind of civic muscle communities rely on in times of need.

Foundations for FUTURE PROGRAMS. The tomato-club model helped shape cooperative extension culture and youth programs that still serve rural America.

LIMITS AND LESSONS

Equity matters. Early participation often mirrored the exclusions of the era, including segregation and uneven access to equipment and instruction. A modern revival must be intentionally inclusive—across race, class, and geography—and eliminate resource barriers.

Labor and logistics. Garden and canning work adds to domestic labor; success requires fair sharing, proper tools, and community infrastructure (training, equipment libraries, safe kitchens).

WHY THIS HERITAGE MATTERS NOW

Girls’ tomato clubs demonstrate how practical food education can strengthen health, resilience, and dignity at home and across a community. For Cucina di Madre Terra, they offer a powerful template: teach cultivation and preservation, honor seasonal abundance, and connect youth to ancestral skills that sustain families through good years and hard ones.

Reviving the spirit—through school gardens, intergenerational canning days, seed-saving circles, and micro-enterprise projects—relinks today’s kitchens to the wisdom of the past while addressing modern challenges: nutrition gaps, food waste, supply shocks, and the loss of everyday food skills.

HOW COMMUNITIES CAN APPLY THE MODEL TODAY

- SIMPLE SCALE: Start with small, manageable plots or container gardens and a single crop suited to local conditions and preservation.

- SAFETY FIRST: Offer hands-on training and shared equipment for canning, fermenting, and drying with up-to-date guidelines.

- LEDGERS THAT TEACH: Have participants track inputs, yields, and costs to build numeracy and practical planning skills.

- SHOW AND SHARE: Celebrate results with tastings, pop-up markets, and recipe swaps; invite elders to teach family techniques.

- EQUITABLE ACCESS: Provide no-cost seeds, tools, and kitchen access; design programs that welcome all genders and backgrounds.